This article provides an overview of the process for applying for membership in lineage or heritage societies using two examples of such applications, one for the Dakota Territory Pioneer Certificate issued by the Red River Valley Genealogical Society (and other Societies in the Dakotas) and a War of 1812 Heritage Society application issued by the Ontario Genealogical Society.

A fun and rewarding exercise for applying and improving your documentation and genealogical proof standard skills is to seek membership in a Heritage or Lineage Society. There are hundreds of such organizations or certificates in North America. They range from the well known and prestigious, such as the United Empire Loyalists in Canada, the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution, and the General Society of Mayflower Descendants to the obscure and sometimes quirky such as the Flagon and Trencher: Society of Descendants of Colonial Tavern Keepers and the Baronial Order of the Magna Carta. I have found several lists of these societies online which are fun to peruse 1. The Ontario Genealogical Society sponsors seven such societies including the First World War Society (also the Honouring our Heros certificate, which seems to have very similar prerequisites), the Fathers of Confederation Society, the War of 1812 Society, the Centenary Club (100, 150 and 200 years in Canada categories), the 1837 Rebellion Society and the Upper Canada Society 2.

The forms and applications which must be completed vary from organization to organization, but in all cases consist of two main sections. First they require a well documented case that the ancestor qualifies under the society’s eligibility criteria. Second you must provide a full proof of descent to the applicant using genealogical standards of evidence 3. When working backwards several hundred years, which membership in many of the societies will require, you may have to become adept at cross referencing multiple derivative, secondary and indirect sources in the likely absence of a full suite of original, primary or direct sources.

Because I was born in Scotland and have exclusively British ancestors of relatively humble backgrounds, none of the North American heritage or lineage societies appeared to be available to me. This is despite having extensively documented 31 of my own 32 five x great grandparents (#32 was an undisclosed out of wedlock father). The same cannot be said for my wife Diane, as I have traced multiple branches of her family back to 1600s Quebec and France and others to the 1800 to 1810 Mennonite migration to Upper Canada from Pennsylvania. It was therefore with her ancestors that I decided to try my hand with heritage society applications.

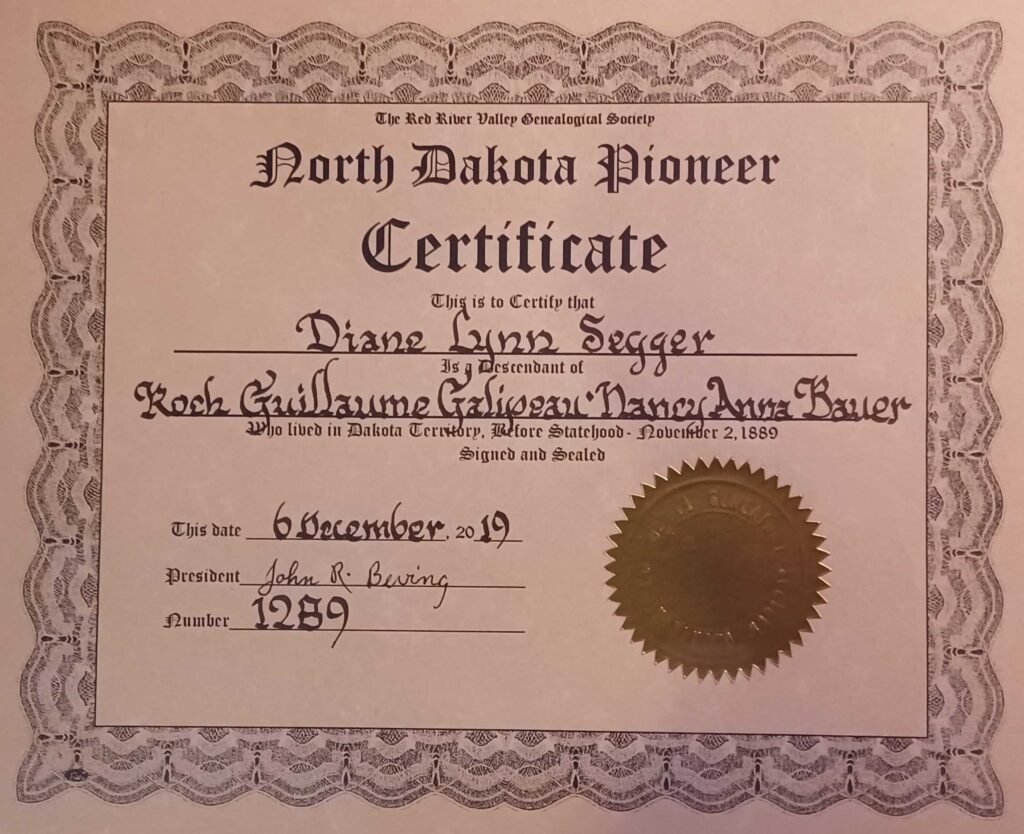

The first certificate I applied for was a fairly obscure one, but one which I felt might resonate with the grand children and also our American snowbird friends in Florida. It was the North Dakota Pioneer Certificate, issued by the Red River Valley Genealogical Society, and granted only to descendants of homesteaders resident in Dakota Territory before statehood on November 2, 1889. Diane had two such families as ancestors, both of whom had migrated from Canada to Dakota Territory. The families were seeking quarter section farm land grants in the decades before statehood (Diane’s direct line ultimately moved back to Canada in 1900). I had reasonably good census, birth, marriage and death records, but this application pushed me to go further and also seek Declaration and Petition records and township land surveys relating to their parent’s claims for farm land. This application also had the advantage of requiring only four generations of documentation. After completing the successful application, the handsome parchment certificate arrived, and has been very popular in the family.

My next such goal was to obtain one of the Ontario Genealogical Society’s heritage certificates. I was relatively confident that an Upper Canada Society certificate was within grasp (ancestor in Upper Canada before the 1841 name change to Canada West) through several family branches, as would Centennial certificates. As appealing as that was, what I really wanted to search for were any connections to the War of 1812. My own historical interests and all of the fairly recent attention to the bicentennial of the War of 1812 dictated this approach. It did not take too long to establish a direct connection, not only to the war, but to the unfortunate Battle of the Thames near Moraviantown where Tecumseh died. Two of Diane’s ancestors, four x GG Jacob Bechtel and 5 x GG Henry Wanner, Sr. had wagons and teams impressed to carry supplies for the British military. I excitedly downloaded the application papers but then, just as quickly, hit a troublesome stumbling block. The War of 1812 certificate states that the ancestor had “fought” in the war, and the criteria specify that the ancestor be:

– a

British soldier based in what is now Canada during the War of 1812-14

– a member of any Canadian militia unit that saw action during the War of

1812-14

– a native who saw action on the British side during the War of 1812-14

Diane’s ancestors were Mennonites and therefore members of one of the “peace churches” who were exempted from bearing arms under provisions of the Militia Acts. Theywere, however, still required to place themselves in the face of danger carrying supplies for the troops by the 1809 Act for Quartering and Billeting, on Certain Occasions, his Majesty’s Troops, and the Militia of this Province. With some encouragement from an OGS employee and one of the Society’s external evaluators I decided to proceed with the application and ask that the certificate be amended to read “who served to preserve the freedom of Canada” rather than “fought to preserve ….”.

See accompanying article on Jacob Bechtel for the detailed story of his involvement and that of 19 other Waterloo area Mennonite farmers in the retreat from Detroit, along with full citations and references.

I’m happy to report that the application was successful, opening up potential society application opportunities for thousands of other descendants of these 20 men.

There were two nagging questions which worried me a little throughout these application processes. These related to the security and ownership of the detailed genealogical data provided to the societies. The exhibits submitted included substantial amounts of under 100 year data relating to living individuals. I’ve always been very cautious about such data, even when communicating within our own families. A very good question which should be addressed to the administration and Boards of these societies is “how do you store and protect this data from unauthorized access?” Larger organizations like OGS will hopefully have the resources to do so responsibly, but many of the smaller lineage societies have few if any staff, and are often managed by volunteers who turn over frequently. Ownership of the data is always another concern for me. OGS asks, in their application, whether you are willing to share the names of the ancestors in Newsleaf and your contact information with other researchers.

I encourage amateur family historians to try to identify qualifying ancestors, and then seek a heritage or lineage society membership. The discipline of completing the application will certainly help you to identify gaps in your sources and greatly improve the documentation of your family tree.

____________________________________________

1 https://www.cyndislist.com/societies/lineage/ ; http://lineagesocietyofamerica.com/list-of-lineage-societies.html; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_hereditary_and_lineage_organizations all accessed 28 December 2018

2 https://ogs.on.ca/about/heritage-societies/ accessed 28 December 2018

3 Brenda Dougall Merriman, Genealogical Standards of Evidence: A Guide for Family Historians, Toronto, Dundurn Press, 2010 provides an excellent overview of the standards