I recently encountered a story which describes a most impressive and unique navigational accomplishment. The facts were presented in a convincing and unquestioning manner, but as is my habit, I decided to dig a little deeper.

An article in the Vancouver Province of May 4, 1942 first reported the story. It has been reworked a number of times since including in recent social media posts, which is how I learned of it. Below is the 1942 article.

A Navigation Feat by Ronald Kenvyn

Can a ship be in two places at the same time? Under certain conditions the answer is “yes.”

Captain John Duthie Sydney Phillips was the shipmaster who managed this unusual feat of navigation. For some 15 years Skipper Phillips commanded liners on the Vancouver-Australia run. He was born aboard his father’s sailing ship, the John Duthie, in Sydney harbor, hence his name. He “served his time” in the famous wind-jammer Port Jackson, which he describes as “the ship that made a sailor out of me.”

Now a resident of Sydney, Captain Phillips has been looking through his old log books and he has produced the record of a remarkable incident which he has forwarded to friends in Vancouver. It deals with the international date line which puzzles passengers. They turn in at night and find on waking that they have lost a day.

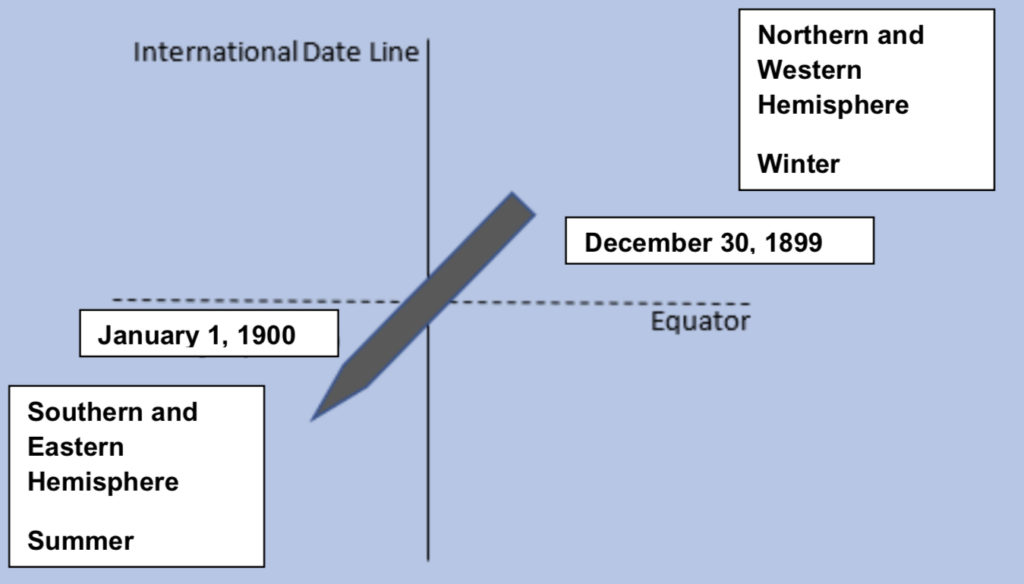

This line, where a change of date occurs, as adopted by the British Admiralty, is a modification of the 180th meridian. It is drawn so as to include islands of any one group on the same side of the line or for political reasons. In these latitudes [Vancouver], for instance, the date line runs just west of the Aleutians. It bisects the equator between the Ellice [now Tuvalu] and Phoenix [now Kiribati] islands and it was there that Captain Phillips put his ship in two places at once.

He was in command of the Warrimoo bound from Vancouver to Brisbane. Early on December 30, 1899, his second-in-command, now Captain F. J. Bayldon, pointed out that if he cared to alter the ship’s course a degree or two and suitably adjust her speed, she could cross the 180th meridian where it intersected the equator exactly at 12 midnight.

This prankish idea appealed to Captain Phillips and the necessary orders were given. Five experienced navigators took careful observations of the sun when it was visible and of the stars at night. The ship’s position was checked every three hours and she reached the appointed spot at the appointed time.

And here is what happened:

The bows of the Warrimoo were in the southern hemisphere but her stern was in the northern hemisphere.

One side of her was in the western hemisphere, the other in the eastern hemisphere.

Passengers and crew in the forward part of the ship were living in Monday, January 1, 1900 while passengers and crew in the after part were still in Saturday, December 30, 1899, having not yet “lost a day.”

And those aboard were the first people on earth to hail the new century and the last to bid the old century farewell.

“Syd Phillips does not think this feat will be duplicated because it’s a long time to the next century!”

While this nifty navigation is theoretically possible, and as remarkable and educational as the story may be, it should perhaps be taken with a small grain of salt.

- The story was not told by Captain Phillips until 40 years after the event. No hint of the accomplishment was publicly reported at the time of the crossing or subsequently by any of the crew or passengers.

- No actual log books have been published.

- The navigational techniques of 1900, as described in the article, were not accurate enough to place the ship precisely on the spot reported.

- It may be a minor quibble, but the twentieth century did not actually start until one year later on January 1, 1901.

- A January 10, 1900 article announcing the arrival of the Warrimoo in Sydney, Australia stated that she crossed the equator on December 30, 1899, establishing some plausibility for the tale.

- To add to the list of anomalies listed in the Kenvyn article, the passengers in the front were in summer and the passengers in the aft were still in winter.

- Mariners whose ship is navigated to this geographic spot (0.0° N, 180.0° E) so as to be in all four hemispheres at the same time are referred to as Golden Shellbacks (a Shellback has crossed the equator in a ship).

- The International Date Line actually crosses the equator three times due to some jogs introduced to keep political entities in the same time zone.

- I searched for any reports of ships trying to replicate this feat on December 30, 2000 without success.

Readers interested in identifying sources for learning more about the mysteries of the lines of latitude and longitude and navigation on the high seas may wish to read the accompanying review of a couple of books I have enjoyed (see Nautical Writing section).